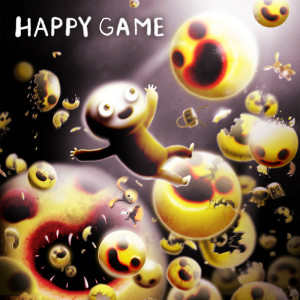

Review for Happy Game

“Please note: Happy Game is not a happy game,” reads the introductory text to Amanita Design’s new horror puzzler, and boy howdy it is not kidding. About halfway through I thought I might need to get up and take a break for a bit, so unrelentingly bleak was its atmosphere, but as with all good horror stories I knew it wouldn’t help: it would still be sitting there, waiting patiently for me to come back. Happy Game may be the brainchild of developer Jaromír Plachý, who headed up such past Amanita projects as CHUCHEL and Botanicula, but don’t let its pedigree, simple gameplay and cartoony aesthetic fool you: this is so far removed from the bright, all-ages fun of those titles that it’s practically in another galaxy.

The question to ask, then, is whether that sounds like a good time to you. If it does—and make no mistake, my answer was and continues to be “Yes”—then odds are you’ll find a lot to like in Happy Game. If it doesn’t, though, there’s almost no chance that this will turn out to be the game for you. Proceed accordingly.

Happy Game opens with an unnamed little boy laying down to bed in his darkened room. His sleep is immediately disturbed by nightmares about traumatic losses he’s suffered: the theft of a soccer ball by a schoolyard bully, the accidental loss of his stuffed bunny while playing by a lake, and the disappearance of his dog during a game of fetch in the woods. Your job is to guide him through his nightmares and regain what was lost, finding ways to overcome the horrific creatures and scenarios that his subconscious throws into his path.

Each nightmare takes place in its own distinct landscape, with unique imagery relating to the object and emotions that inspired it. In the first, the boy chases after his ball through a dark, largely monochromatic playroom full of demonic toys; in the second, he tries to rescue his bunny from the jaws of a giant, cannibalistic rabbit-monster in a circular, deceptively sunshiny countryside; in the third he travels with his dog through a monster-haunted forest. Aside from the constant recurrence of blankly staring smiley-face creatures, there’s very little connecting the three segments; they play, essentially, like themed levels.

Amanita understands the expectations players will have coming in and does its best to subvert them at every turn. The Czech developer’s previous titles have typically succeeded on the strength of their by-now-familiar formula: inviting us into a fabulous, lively world to tinker with abandon, with no exposition or explanation beyond what can be observed from direct experience. With the freedom to explore and experiment came a constant parade of pleasant surprises waiting around every corner, infused with a spirit of playfulness and adventure. Here the same principle applies, but fills each screen instead with dread and the certain knowledge that everything you see is much worse than it looks. Children’s toys contain dark spirits that look to be sculpted from old, clotted blood; playful, smiling elves laugh hysterically when one of their number explodes and dies; a smiling face can never, ever be trusted.

The imagery is overwhelmingly of innocence, happiness, and positivity perverted. The boy is haunted by the ghostly apparition of a glowing, bruise-colored smiley face that crops up behind him whenever he’s upset, and the majority of the game’s most horrific set pieces involve similarly beaming monstrosities. You’ll witness any number of decapitations, eviscerations, head explosions, and amateur surgeries, all carried out by brightly colored, blank-eyed perpetrators wearing friendly grins—or, worse, by your guileless, unwitting avatar. It’s all grimly effective, almost to the point of being exhausting; thankfully the game limits itself to an abbreviated playtime of maybe two hours in total, seeming to understand how easily it could overstay its welcome.

All this horror is in service to an interesting central metaphor about denial, the fragility of a child’s psyche, and the paradoxical way that attempts to shelter them from the world tend to worsen their inevitable disillusionment. Our boy wants desperately to be happy, and he doesn’t know how to handle the shock of learning that it’s not that easy; his grinning shadow is always waiting to zonk him into unconsciousness when tragedy strikes, a seeming embodiment of all the platitudes we feed children because it’s easier than explaining how the world works. But bucking up and smiling through the pain rarely solves a problem; rather, it gives it the camouflage it needs to creep stealthily into one’s subconscious and stick there.

At the heart of all of the game’s imagery is the conflict between what the boy wants and believes is possible—a happy, smiling world that can’t harm or threaten him—and the sad, scary reality that pain and disappointment are a part of life. He unfortunately lacks the capacity to process or understand the heartbreak he’s only just beginning to experience, and as the game progresses we see his limited toolkit continually fail him. Everywhere you turn you’ll see hastily erected facades covering up disturbing realities, ready to fall away at the slightest touch, and whenever the boy seems about to enjoy himself, something crops up to remind him that his problems are still there and growing.

The art style effectively foregrounds this conflict, striking a delicate balance between the warm, friendly images the boy initially perceives—a sunny field full of cavorting bunnies; a playground for laughing, childlike sprites with heart-shaped heads; a series of cuddly-looking toys—and the violent menaces that lurk just beneath their surfaces. There’s a solid, tactile quality to the characters and objects; it almost seems like you could reach through the screen and touch them. Every wound, severed limb, and spraying ounce of viscera has a weight to it that’s at odds with the cartoonish world of which it’s a part. The colors are vivid and used to great effect, especially in the middle third. Naturally there’s a lot of red, to the point that it’s the only color in several sequences, but the developers wring a whole palette’s worth of different shades from it.

Amanita is famous for its creative approach to sound design, where incomprehensible babble stands in for dialogue, and various snatches of music, foley effects or amusing noises take the place of standard environmental ambience. Happy Game is yet another triumph in this regard, with an uncomfortable array of squishes, sloshes, and splats bringing each horrific happening to cringe-inducing life. The boy’s tremulous mutterings tell us everything we need to know about his personality, while a variety of unearthly hums, drones and groans lend a threatening undertone to even the most innocuous dreamscape. The synth score by frequent Amanita collaborators DVA is stellar from start to finish: tranquil tracks with flavors of xylophone and theremin create a calm, contemplative atmosphere that almost manages to convince you you’re out of danger, only for screeching industrial feedback and howling sirens to signal the arrival of some new threat. The main theme, backed by the ethereal chanting of a children’s choir, speaks rather heartbreakingly to the child’s longing for warmth and comfort.

If Happy Game has one major failing, it’s the way the final act largely abandons the motif of smiles hiding screams that’s served it so well and instead brings monstrous darkness into the foreground. The happy veneer falls almost entirely away from the third nightmare, leaving the boy to wander sparsely colored fields and swamps while butting up against a continuous parade of malicious entities. There’s nothing wrong with this, and it might be in keeping with the central metaphor as the boy loses his innocence entirely, but as executed it makes the game feel less interesting than it has up until then. These monsters are all quite similar in design, to the point that they feel almost interchangeable, and the color palette is so drab and unvaried that it becomes visually unengaging. It feels like the beguiling game about childhood fears and purity shattered has given way to a much simpler one about being menaced by demons. It’s a disappointing turn, and it had me longing for the kind of extreme discomfort the earlier segments evoked.

As with much of Amanita’s work, Happy Game doesn’t have rich gameplay to fall back on when the quality of its atmosphere starts to dip. The controls are incredibly simple, with a single hand-shaped cursor that widens to indicate you’ve found a hotspot. Sometimes you can manipulate or move objects to where you need them by clicking and dragging, but more often you’ll simply select a hotspot to activate it and wait for it to do what it does. You don’t even have to pick where you want the boy to go; simply clicking on him and holding the button down will prompt him to walk one way or the other until you let go, depending on the direction you move the mouse or gamepad stick.

The puzzles are mostly secondary to the experience of these nightmare worlds; in most cases there are only a few things on-screen to interact with and little room to maneuver, the challenge being to figure out how to make them fit together. This never takes too long, as everything you need is usually in sight or within a few steps of where you’re standing. Our young protagonist can pick objects up and hold them over his head as he moves, but he won’t ever have to go very far to find where they belong. It’s mostly a matter of clicking, observing, and repeating until you’ve intuited how to make the next thing happen. With so many sharp blades and hungry maws lying about, it is possible to die, but doing so will only send you back to the beginning of the current puzzle or set piece; the game saves your progress automatically along the way.

Happy Game knows it isn’t for everyone, and part of what makes it so interesting is how far its tone strays from everything the studio has produced in the past two decades; Pilgrims and Creaks began a noted trend toward darker, edgier titles at Amanita, but here we go far beyond where even those games dared to tread. Full to bursting with cartoon gore as it may be, though, nothing it does ever feels gratuitous; every dram of bunny blood is spilled in service to its well-considered central metaphor about the horrors of growing up and the inadequacy of wholesome, happy vibes to banish darkness on their own. It has its shortcomings, but there’s a lot to enjoy here if you’re drawn to disturbing subject matter. If you’re not ... well ... have you ever heard of this neat little game called Samorost?