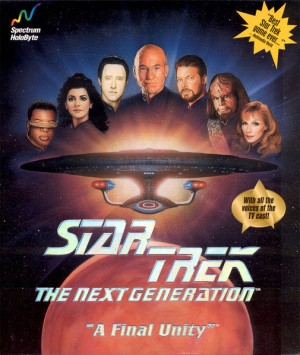

Star Trek: The Next Generation – A Final Unity flashback review

With the return of legendary Starfleet Captain Jean-Luc Picard in his own new Star Trek television series, it seems a fitting time to flash back to The Next Generation’s heyday and Spectrum Holobyte’s 1995 point-and-click adventure, A Final Unity. This entry into the franchise gaming library remains faithful in most ways to the series it’s based on, for (mostly) better and (a little) for worse. Even 25 years later, it holds up as both a quality Star Trek game and a solid science fiction adventure in its own right, although it does assume a passing familiarity with the show so if transporters, tricorders, phasers, and warp drives are unfamiliar to you, best to turn back now. At least, it does if you have the patience to wade through the first couple of troublesome missions.

A Final Unity is an oddly structured game, as most of its problems come at the start. It opens with computer generated video aboard the Enterprise that appeared dated even at the time of release, with characters looking like partially melted plastic dolls. From there it moves into a dialog puzzle between Picard and an enemy captain that will more likely than not lead directly to the game’s absolutely terrible space combat simulator. After that, things settle down a bit with away team missions and actual point-and-clicking adventure.

Even then, however, it’s still a bit of a slog for a while as the first mission is rife with technobabble, requiring a science researcher to tell you what to do step-by-step with an assortment of inventory items with such helpful names as plasma shunt, flux router, wave converter, inverter coupling, graviton probe, and pulse negator. The second mission is a mystery investigation into the disappearance of a zoologist but it fares little better, with lots of tedious waiting due to long walk distances, slow animations, and drawn-out conversations that must be conducted in a specific order. Even fans of the show may be hard-pressed to make it through these early portions.

Fortunately, matters improve significantly with the third mission. Puzzles become much more reasonable, with sufficient direction provided and enough context for players to deduce how things work without being led by the hand (although occasional bouts of technobabble still show up). Space combat becomes much easier to avoid, and the mandatory battles are not as difficult to win as the very first one. It’s at this point that A Final Unity settles into a more generally appealing adventure format, although with a few Star Trek touches to spice things up.

The story takes place across seven away team missions, taking me six hours even on a replay, though you can probably expect to double or even triple that a first time through. Each mission has four crew members from the Enterprise beaming down to a planet, with different personnel bringing different skills and inventory items with them. For example, the android Data and engineer Geordi La Forge are more technically inclined and can operate equipment that others can’t. Doctor Beverly Crusher gets the added benefits of having a medical tricorder for patient analysis and a portable medical kit for treating people.

The game features three difficulty levels that impact the away team structure. On Ensign, the crew members and their equipment are assigned automatically, with no opportunity for player input. The Lieutenant level also automatically arranges everything by default, but gives the player the chance to make changes. On Captain, players have to select which characters and gear they want to take with them from scratch. Choice of away team members is important, as some puzzles may require alternate solutions or may not be doable at all without the right people, requiring the mission to be restarted from the beginning.

Although the away missions are self-contained, in between a number of ship-to-ship and ship-to-base encounters on the bridge of the Enterprise herself, there are several narrative threads woven throughout to form a more cohesive story overall. The tale begins with a Garidian starship pursuing one of its own scout ships from the Romulan side of the neutral zone into Federation space. (The Garidians are a new alien race created for the game that are essentially just Romulans living on the planet Garid). It turns out the scout ship members are revolutionaries looking to improve living conditions on their home planet and have escaped seeking asylum. This through line comes and goes right into the final episode. As it does, you’ll learn more and more about an ancient alien race called the Chodak, who once had a galaxy-spanning empire thanks to something called the Unity Device, a machine of awesome creative and destructive power that was cast away into the time stream millennia ago. Now rumours of the Unity Device’s return abound, and of course several superpowers are interested in acquiring it.

Most of your time will be spent in away team missions, however. A tool bar is present at the bottom of the screen during these sections that provides buttons for walking, talking, interacting, and examining in typical point-and-click fashion. Inventory items are also shown in this part of the display, along with a couple options unique to this game. There is a character portrait button that, when clicked, cycles through each of the four crew members on the current mission. Players only ever directly control one person at a time, but all of them move together through the different locations. There is also a power bar for setting how strong the away team’s phasers are. Although there are a few situations where the crew can die (bringing the game to an end, so be sure to regularly avail yourself of one of the nine manual save game slots), there isn’t any ground-based combat per se. Instead the phaser is used more as a tool and provides the solution to a couple of puzzles.

Away missions provide a lot of variety, both in the locales visited and the tasks that must be done. A damaged space station, with its metal panels and computers, requires technical expertise to fix its broken systems. An ancient Chodak outpost, now an archeological site, is hewn from a planet’s rock and now requires careful examination of various old machines to gain key navigational insights. A world hosting a group of Garidians that fled their homes in years past has splintered into various religious and philosophical groups, requiring a bit of diplomacy and problem-solving ability. The various temples on this planet are as different as the philosophies behind them, with one containing bubble-shaped, biological musical instruments, another that’s all glowing green spikes and sharp edges, and yet another possessing ancient machinery hidden in stone statues.

The developers of A Final Unity are on record as saying they wanted to give players the sense that they were really on a voyage with the Enterprise crew. To do that, they modelled a large 3D cube of space, allowing you to plot a course and fly anywhere, although only the systems relevant to the storyline actually have planets that can be explored. While certainly an admirable goal, this ambition comes with a downside. To better convey the sense of moving through space, whenever a course is laid in, the ship’s viewscreen is displayed and players can do nothing but wait and watch the stars zip by while flying to the destination. Ordinarily, Picard orders a relatively slow warp speed, so this can last several minutes by default. Fortunately, the target location can easily be reselected and the warp factor manually increased to maximum, which reduces the waiting time significantly, although it doesn’t eliminate it entirely.

The operations and weapons systems are also extensively simulated when the ship enters combat. There’s no easy way to describe the combat interface because it’s so convoluted. When the game originally released it came with a rather hefty manual with over twenty pages devoted solely to battle. Players can fly the ship directly, choose specific maneuvers, target and scan enemies, review damage to the Enterprise, assign repair teams, manage power distribution (it’s a bad thing when the shields run out of power), fire weapons, and so on. Thankfully, the game allows all tactical decisions to be turned over to the Klingon weapons officer Worf, and all engineering/damage repair concerns to be handled by Geordi. But you still have to sit and wait for any combat scenarios to play out and hope the Enterprise doesn’t get destroyed, as that’s game-over. Worse, any damage sustained during firefights can impact the non-combat portions of the game. For example, if the warp drive gets damaged you won’t be able to travel at maximum speed, assuming you can warp at all, until Geordi repairs it, which again requires waiting.

Visually the game was quite respectable back in ‘95, pre-rendered CG videos aside. It came out in that period where adventures were just starting to transition from the low resolution of 320x200 to high-res (for the time) 640x480, which A Final Unity employs. With over four times the pixel art detail, characters are easily recognizable from their TV counterparts and look around when idle, take tricorder readings, or fidget in other ways while on away missions. Background animations are quite frequent, whether animals roaming in the distance in a nature preserve or robotic drones floating through the air in an ancient factory.

Ship battles use early texture-mapped 3D models that look quite decent, but due to the limited horsepower of computers at the time, the space combat view is relegated to one small corner with ship’s systems and controls taking up the bulk of the screen’s real estate. Fights are conducted at long range so vessels tend to appear very small unless the Enterprise or her opponent are destroyed, which then gets a brief, close range “death cam” view. Phasers and photon torpedoes are simply represented as either 3D lines or round, glowing stars respectively.

Audio is also done quite well. A major coup was achieved when the developers got all seven principle actors from The Next Generation to voice their characters in the game, as well as Majel Barrett providing the voice of the computer just like in the series. All of the screen actors do a fine job of moving into the realm of voice-overs, and an excellent voice cast for new characters is introduced as well, with Garidian Commander Pentara and Chodak Commander Brodnak being stand-outs.

A great deal of ambient sound is used throughout the missions and matches the locations extremely well. The nature preserve features several different biotopes, so rain, wind, and various animal sounds abound. Deserted archeological sites have echoing reverberations that convey the proper sense of scale of their large spaces. In contrast to the planet missions, sound in space battles is very scarce, limited essentially to the firing of weapons and ships getting hit. Curiously, very little music is employed throughout the game except for the cinematics, including the series’ theme song during the game’s intro. Ship battles have no accompaniment and even away missions have only occasional short musical stings.

Star Trek: The Next Generation – A Final Unity will appeal most to fans of the show. With the full voice cast and with a wide variety of missions available, this is an adventure that remains very faithful to its source material. And yet while familiarity with the series is certainly beneficial, there is also a decent point-and-click game here for fans of science fiction adventures in general. It’s unfortunate that most of the poor design choices appear early on, but if you can slog through the prologue and first two missions, the bulk of the gameplay experience afterwards is much more rewarding. A quarter century after its release, this game still holds up as a fine entry in the Star Trek universe and a largely fun adventure in its own right. To paraphrase Captain Picard himself: Let history never forget the game…A Final Unity.