Return to Zork flashback review

Recently Return to Zork, a game from 1993 that broke free of the series’ text adventure roots and into the realm of point-and-click FMV, celebrated its 25th anniversary. After revisiting RTZ all these years later, I still found myself awestruck when, after an elaborate whisky toasting sequence, I managed to escape the grim reality of West Shanbar through a secret trap door and ended up in a magical underground world of wizards, illumynite, enchanted forests, and darkness-dwelling grues. But while I look back on the game with fond memories, some elements have withstood the test of time better than others. Though the graphics and animations now appear dated, the game’s unique Zorkian humour remains funny, and the scope and size of its explorable world is still commendable. No amount of starry-eyed nostalgia, however, can blind me to the one vital issue afflicting Return to Zork – namely that its puzzles, while often hilarious, are not so much challenging as they are recipes for madness. To those who are interested in Zork’s place in genre history, you will find this adventure a fascinating and unique experience unlike any other, but for the vast majority of gamers just seeking an enjoyable point-and-click from the ‘90s, I cannot recommend it without significant caution.

In keeping with Zork tradition, the game begins in front of a white house. As you move to the west and open a mailbox, you find a tele-orb and receive a call from a man claiming that you have won the sweepstakes. Although this sounds like good news, the man is suddenly interrupted by an evil force and you are magically whisked off to the Valley of The Sparrows, a desolate land now plagued by killer vultures. You soon find yourself stranded near a lighthouse and a southbound road that, according to the lighthouse keeper, is “impassable, absolutely impossible to pass.” Only after finding a way to sail a river downstream will you get to West Shanbar, a town that has fallen into disrepair following the mysterious disappearance of most of its residents. Eventually you make your way to the Great Underground Empire (GUE), where you find the missing Shanbarians and learn that the realm is being corrupted and taken over by evil magic in the embodiment of the dream-stealing Morphius.

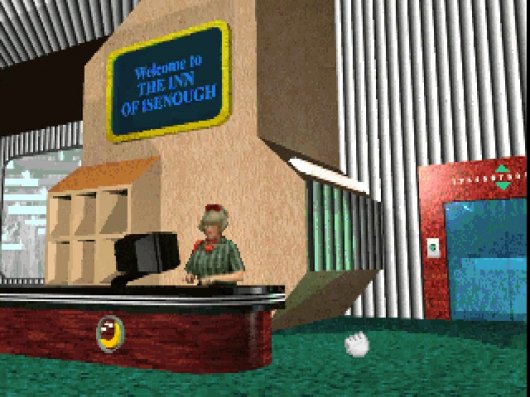

The way RTZ’s story is told is one of its most beautiful elements, and at the same time one of its greatest weaknesses. Much of the detail that fleshes out this world’s backstory requires you to read large amounts of information from file cabinets and notebooks, and to show every conceivable picture, recording and item in your inventory to every other character you meet. The more time and effort you put into RTZ, the more you will learn. The issue here is that it is possible to easily overlook many interesting aspects of the narrative, along with a large number of details that, while not vital to know, add to its believability and depth. Showing the tele-orb to one character, for example, leads to dialogue about the partnership of those who made the orb and the purpose for which it was created, whereas showing a picture of a school teacher from the upper world to a hotel receptionist in the GUE returns a fair amount of useless but interesting gossip. Rely too much on a walkthrough, as the dastardly puzzles will likely tempt you to do, and you could miss much of the concealed information designed to enrich the Zork experience.

Return to Zork has a large cast and many are instrumental in providing relevant details. The state of the GUE, past events of the Grand Diffusion, and Morphius’s rise to power are recounted through characters such as Rebecca Snoot the writer, and Moadikum Moodock the one-armed arms dealer. There are also other minor roles including trolls, a marsh-dwelling witch, and fan favourite Boos, who spawned a catchphrase with his rhetorical “Want some rye? ‘Course ya’ do!” The key plot points, however, are conveyed by your travelling companion, the wizard Trembyle, who frequently calls you on your tele-orb to regale you with the history of magic and the GUE. The villainous Morphius is probably one of the weaker characters, despite the excellent voice talent behind him. While the first encounter with Morphius reveals the pleasure he takes in terrorizing humans in their dreams, you have little other contact with him throughout the game. He is far from fearsome in your initial meeting when he appears as a floating blob-like apparition, though he does show himself to be more of a worthy opponent later on.

Although it has been re-released through digital distribution, RTZ has not been remastered and remains nearly identical to its 1993 release, with only one change. The original version came with a hard copy of the Encyclopedia Frobozzica, a large booklet full of hilarious Zorkian lore that was required to answer questions within the game on two occasions. In doing so, the book doubled as a physical copyright protection device, making it impossible to progress far if you did not have it. Now these tests have been amended to very simple questions whose answers can be found quite easily while playing. Despite the fact that it is now obsolete, this amusing Encyclopedia played a vital role in the original experience, and it is still digitally provided on some PC platforms today (GOG, but not Steam).

The FMV visuals and animation were truly incredible in their day, and I recall thinking that the graphics were the most realistic I had seen to that point. In retrospect, however, certain elements and characters sometimes appear unconvincingly superimposed on their environments, such as Mrs Peepers the school teacher, who unnecessarily dominates most of the screen within her classroom. Facial animations are also bizarre, as expressions and mouth movements appear to be superimposed from snippets of pre-recorded acting, leading to some strange, unnatural interactions. Particularly important moments of dialogue are actual FMV clips, but these are used sparingly in an effort to conserve memory, an important factor considering the systems of most gamers at the time. Despite looking somewhat dated now, some of the scenery is still somewhat charming, particularly the marsh and forest mazes which remain quite beautiful and fun to get lost in.

Players move through RTZ in first-person slideshow fashion, and doing so often results in FMV transitions between areas, lending a seamless dimension to navigation. One of the most impressive examples of this is when, with the help of the wizard Canuk, you are shrunk down to tiny size and lowered into a ship inside a glass bottle to retrieve an important item. I remember that when I first played the game in the mid ’90s, this descent into the bottle was a very special moment that felt phenomenally realistic at the time. While even this sequence now looks antiquated in comparison to modern titles, I still found my revisit down the bottleneck convincing and I give the developers credit for this creative idea.

The audio in Return to Zork is diverse, with a high quality that has aged less poorly than the visuals. The music ranges from simple midi-style tracks to the more resonant tones of the ominous main theme. All characters in the game are voiced and at times the acting is very good, while occasionally it is merely tolerable but rarely poor. Sound effects are basic and are sometimes comical representations of the actions you are performing, such as the pull whistle that is periodically played when you throw an inventory item.

The multiple interfaces in RTZ are all noteworthy as they provide varied interactions in a way that was new and thoughtful at the time. Take, for example, the communication system that allows you to click on buttons of facial expressions to steer the direction of a conversation while another character is talking. Because the unseen protagonist never speaks, these social cues are an effective means of communicating without ever requiring a verbal response from the player. The available buttons to choose from differ depending on the particular dialogue, but mostly you have the option to appear fascinated, bored, cautious, or threatening. This system not only fleshes out the characters and advances the story, but also enables you to find hints and solve puzzles by using the buttons at certain times and in specific sequences.

Another remarkable feature is the breadth of highly specific possibilities when interacting with characters, items or objects. From the beginning, you have the ability to take photographs of almost any screen, while automatically keeping tape recordings of what other characters have to say. All photos, voice recordings, inventory items and places on your map can be shown to anyone in the hopes of acquiring a clue on how to progress, though most of the time these combinations will not return a response. The inventory system is also different than other point-and-clicks, consisting of a diamond-like interface that appears whenever you try to use an item with another hotspot or character. This means that instead of the object simply taking effect, here you are asked to specify the purpose for the item in context. Such options are many, varied, and tailored to pairings of all sorts. One case of this is in a wizard’s hut, where you use a scroll on a duck and are allowed to choose between “Throw Scroll at Duck”, “Read Scroll to Duck”, and my personal favourite, “Feed Scroll to Duck.” This system stemmed from the advanced text parser of previous Zork titles, and it makes the world feel full of opportunity.

One of the most impressive things about RTZ is its non-linear gameplay, with puzzles that can be tackled in almost any order at any time. After my latest replay, I still feel as though it provides one of the most open-world experiences of any point-and-click adventure, a truly outstanding achievement only tarnished by the inanity of the puzzles. Yes, they truly are beyond challenging – indescribably so. Finding clues and hints is nearly as difficult as solving the puzzles themselves, and when you do come across one it will usually be so obscure as to not be very practical. An example of this is when you, for no discernible reason, decide to show a picture of a cow to a witch on the other side of a river. The witch asks if you’ve ever tried to milk a cow with cold hands, but has no wisdom to offer regarding the extremely convoluted, not to mention dangerous set of actions you need to perform to warm your hands. Since the clues are often cryptic and the hints unhelpful, expect to find yourself showing everything in your possession to every character you meet.

As if the challenges posed by Return to Zork were not extreme enough, there are also several points where your decisions can have sometimes funny, sometimes frustrating consequences that make the game unwinnable. Humorous occasions usually lead to your death, such as lighting a match around Boos (the town drunk), or alternatively deciding to give your legendary Dwarven sword to a troll who wants to kill you. Resorting to crime is another guaranteed way of hilariously sabotaging your own adventure, as murder, theft or – seemingly worst of all – opening someone else’s mail will earn you a visit from a mysterious figure known as The Guardian, who teaches you the error of your ways by relieving you of all your items before leaving you to aimlessly wander the world until you decide to reload. With no autosaves to fall back on, make sure to save your progress early and often.

In contrast to these mostly acceptable missteps are those where your game-breaking actions go unchallenged or, even more confusingly, actually appear to progress the story while making the game impossible to complete. As strange as this may be to newer generations of gamers, you can actually ruin your playthrough of RTZ within the first three clicks of starting and not realize until close to the end. There is another occasion where giving an item to a character will cause them to transport you across a river, which seems sensible, except that you need the item to get back across when you’re done on the other side. In this case, giving it away the first time is incorrect, and yet it appears to be the right thing to do, since it’s rewarded by an animated boat journey and new areas to explore. You also have the opportunity to throw any of your inventory items into an incinerator from which, perhaps unsurprisingly, you will never get them back again. Although it would certainly sound reasonable not to destroy your stuff, the game actually requires you to burn one particular object to progress, and it is not altogether clear which item it is.

In terms of playtime, it would be hard to give useful specifics. RTZ was my first experience with the Zork series and I was very young at the time. It took me several months to complete it, and even then I had to refer to a walkthrough for solutions about a dozen times. Without assistance, the expected playtime is truly incalculable, particularly if you hit a dead end.

One thing that can be said for Return to Zork is that it’s a point-and-click adventure unlike any other. To many gamers it may offer more headaches than enjoyment, but often the humour and hint-hunting can keep you going for an extraordinarily long time. While it is nearly impossible without assistance, successfully solving the puzzles on your own naturally provides a sense of monumental accomplishment, virtually tantamount to stopping a train with the power of your mind. To those interested in genre history, on the other hand, it is a textbook example of how not to implement puzzles that venture far beyond the shores of logic and common sense. The term “Zork” was coined in the ‘80s by computer programmers to refer to an unfinished program, a work in progress. The irony is that without help you will likely never finish this game. In the words of the lighthouse keeper: it is impassable, absolutely impossible to pass. So for anyone willing to undertake the challenge, I strongly recommend playing with a walkthrough close at hand – consulting it just often enough to continue without robbing yourself of the opportunity to experience everything the game has to offer.