Review for Quadrilateral Cowboy

Is there anything cooler than the perfect heist? Images of smooth, suave-looking operators taking things that don’t belong to them by always being the smartest people in the room have trained us to expect a lot of fun and adventure in a heist caper. Subverting those preconceptions, the brilliantly-named Quadrilateral Cowboy wants to take the coolness of the heist and make something decidedly nerdy out of it. The game walks you through nine different heists, but rather than a slick dude with sunglasses and charm to spare, you’re a computer hacker doing your thieving old-school techno-style. And in its early 1980s settings, there are no cool Graphical User Interfaces, no User Experience-focused apps to assist you. It’s just the raw black screen and monochrome characters of a computer geek’s terminal, and it’s an incredibly fun, though brief, experience—as long as you can stomach a fair bit of action-oriented gameplay, plus the overwhelmingly postmodern aesthetic that is a signature of indie developer Blendo Games.

All you need to know about the story of Quadrilateral Cowboy is that you play a hacker, because that’s really the extent of the background offered. There’s no greater reason for your escapades, no evil corporation that you’re trying to take out, no context at all for the missions. It appears that you’re part of a team, but the lack of effort and involvement from your teammates is actually a point of comic emphasis; if they’re visible at all between missions, they’re likely to be reading a magazine or tossing a tennis ball, and they have nothing to do in any way with the fulfillment of any mission.

At its core, Quadrilateral Cowboy is a thinking man’s first-person puzzle-platformer that takes place entirely in virtual reality projections where you “plan” your heists. Your character’s movement is fully controlled by WASD with crouch and jump keys, along with numerical keys (or the mouse wheel) used to select the inventory tools that you accumulate; mouse buttons are required only to deploy the items or pick them back up. The first, and most important, inventory item is your trusty “deck”, a handheld terminal that can be opened up on any floor or raised surface and used to control your other items or whatever nearby doors, lasers, cameras, etc. that you can hack into.

Most of the heists first begin with you gaining a new inventory item and thus a new mechanic. The simple use of the deck and the entry of basic commands to open doors or turn off security sensors powers you through the first theft in tutorial fashion. The second job introduces your weevil, a small robotic roving pet that can be dropped through small spaces such as gratings, and then controlled through your deck with a remote video screen accessory that shows what your weevil is seeing, to provide you visibility into unreachable areas and hack into faraway computer plugs. Another heist introduces a suitcase rifle, which once deployed will fire with laser-precise accuracy to press buttons or flip switches far away.

The robberies generally work in three stages, each one adding a gentle additional layer of complexity to the new mechanic you’re working with. The weevil, rifle, and other tools only work in conjunction with the commands you give them from your deck. The very first rifle-related mission might be as simple as aiming precisely enough, done through the use of pitch(x) and turn(x) commands (the x being a number variable) to shoot a button that opens a door. After you accomplish that, further complications are added such as using the wait(x) command (you can queue up multiple commands with waits between them) to pause long enough to move yourself into position to move through the open door. Setting long enough wait times between commands to give you a chance to establish your position is essential, since most doors and sensors only allow a three-second window before activating the security protocols, which will bring about a very quick turret-related death.

It can get even more complex: one of my favorite missions involved setting up the rifle, aiming it, and then setting the command to wait for me to get in position, fire at one button, wait a bit longer for me to get past the first door, then adjust the aim and pitch to fire at a second button, which shuts off the lasers for the three seconds I needed to get past that blockade and get to the treasure. You must get the entire sequence right or you’ll find yourself trapped or dead, either way requiring a restart of the mission. This is a game that rewards meticulous preparation for the sequence of actions necessary, and even with plenty of forethought, you’ll likely find that your initial wait(x) command was too short or your pitch(x) went too far, and small adjustments will be made after each death. These adjustments require patience and a certain affinity for this type of command line entry, so if you have no memory of a day before graphical operating systems, you may not connect with the experience on the same level that I did. Those who recall subscribing to magazines that listed the BASIC code for games, encouraging you to hand-enter that code and then save it to a cassette tape, will be met with a welcome breeze of nostalgia with every entered command.

Things get a little more intricate toward the end of the game, as your motley crew of hackers is disrupted by the game’s singular story beat (which really doesn’t carry any emotional weight, if it’s even intended to, since this is almost the polar opposite of a character-driven experience). After this, the heists are condensed into just one “stage”, but now you actually enter that stage as different individuals with different abilities, such as fitting through tiny crawl spaces, or sawing through locked doors. Your re-entry into these heist simulations as distinct characters “stacks” the actions of each onto the others. To illustrate, in one heist you first need to enter (beginning at zero time) and take care of the door with your current special ability in order to trigger the switch behind it. That switch can only stay activated for three seconds, so your second character (also starting from zero time) has to make a beeline straight for the lasers that are de-activated by the switch, and be ready to run through when the first character’s command processes.

All this added convolution serves more to emphasize the action and timing elements than thoughtful puzzling. It is often less intuitive, and occasionally inconsistent with its own in-game rules. For example, the “planner” character who can move anywhere with no gravity restrictions and appears to have no physical presence can still be killed by security gun turrets. The enjoyment of discovering new uses for your hacker tools is lost with more focus on trial and error, so from an adventure gamer’s perspective, I found the later stages to not be as enjoyable as the earlier ones.

Though I described it as a thinking man’s game, Quadrilateral Cowboy is certainly not a pure adventure. Although the careful thought and planning involved in each heist will test your intellect, you still have to navigate your character through obstacles quickly and carefully enough to avoid triggering the security measures, and will sometimes have to make quick and precise jumps or falls. There are no in-mission saves, which I am fine with, because allowing you to quicksave and then immediately jump back 10 seconds every time you make a slight mistake would be contrary to the spirit of careful planning that the game emphasizes. You try, you plan, you make a mistake, and so you try again with slight adjustments. Then you find your adjustments were too slight, and you try again. Some of the missions could take 20-25 minutes given the necessary patience for making mistakes and re-calibrating your plan, but when you have it all figured out, almost all of them can be speedrun in 2-3 minutes.

If you have above-average skill at this type of game, you’ll likely burn your way through the nine stages in less than my playtime of 5-6 hours and discover the game’s biggest weakness: this is a game that builds a great world and a great framework for complex puzzles, but never actually delivers on the possible complexity. It’s almost as though this is the equivalent of a basic-level college course, teaching you what you need to know about the foundational principles to effectively use everything, but waiting to introduce the effects of really layering the concepts until next year. It’s a credit to Blendo Games how accessible the usage of all the hacking tools really is, and how simple the hacking program language is to pick up (even if the very thought of text coding seems too dense to be fun) but it’s almost more like a prologue to a never-realized grand heist that would take hours and involve incredibly deep stacks of deck commands using all your tools together.

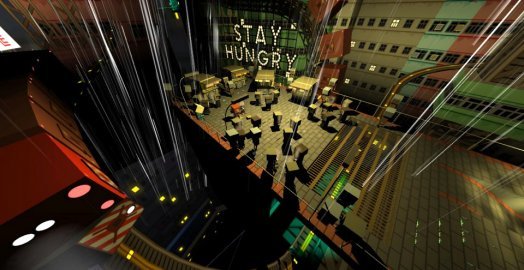

The aesthetic created by Quadrilateral Cowboy is a very unique one. It is not a great-looking game; actually, it’s more accurate to say that it’s not a game designed to be visually attractive. There is a great deal of care put into small details such as stickers on doors, but the floor and wall textures are big and blocky and there is not much detail in the indoor scenery. The environments, at least in-mission, are not very bright or colorful either, but it all converges to form a clearly deliberate minimalist motif. Most of your insertion points are on platforms in the middle of isolated structures with miles of sky visible in all directions, so the missions at least start with some attractive outdoor visuals before getting into the blandness of indoor areas. One practical benefit of the somewhat old-school 3D presentation is that there’s very little to draw your attention away, so you’ll never lose track visually of what you need to focus on.

There is no soundtrack at all during the gameplay scenes, only the ambient noise of your own heavy footsteps, doors opening, terminal keys clicking, and occasionally security turrets making mincemeat out of you. There is some music during the intermission scenes—classical Italian opera, the most non-heist backdrop you could think of, which is actually a pretty brilliant bit of ironic humor.

And of course, it’s worth mentioning that the game takes place in the same postmodern universe shared with other games from this studio, such as Gravity Bone and the incredibly strange Thirty Flights of Loving. The characters—all of whom have the same large cube-shaped heads—are really characters only in the loosest sense of the word. They apparently have names, but they are interchangeable and completely meaningless and they never speak, instead communicating only through head movements and occasional noises.

The peculiar postmodernism shows up in small touches of art design throughout many missions, and in larger touches during the truly bizarre avant-garde intermissions between heist stages. These scenes, which you play through in character, are as simple as walking around your apartment before jumping onto the back of your co-hacker’s cycle that you carpool (bikepool?) to work on, or as unusual as stopping to play a leisurely (and endless, if you’re so inclined) game of first-person badminton on the flower-covered roof of your headquarters. There is nothing in these intermissions that has the slightest morsel of story relevance, but it’s more to allow for some world-building vanity by the designers, and these fillers are where most of the game’s more interesting and detailed visual environments are found. If you’re into the world, you’ll love it, and if you’re not, it always ends quickly and doesn’t distract during the actual “game” parts.

While Quadrilateral Cowboy only scratches the surface of its own potential and ends too quickly, having built a great toolkit without fully discovering the possibilities within, perhaps the best decision of all by Blendo is to allow for the game to be modded. So although your initial playthrough of the game may leave you a bit hungry for more, you’re likely to be satiated by the game’s large fanbase and the certainty of strong output by the mod community, to say nothing of possible DLC or sequels from the developer.

Computer hacking has always been a sport of geeks; even when the cool movie stars in sunglasses assemble their heist teams, the hacker is almost always the marginal, antisocial character in the background. In the modern era, where pop culture touchstones like Mr. Robot are making hacking a cool person’s game again, Quadrilaterial Cowboy makes you feel like the coolest of hackers and, though it’s an incomplete experience, certainly lays the foundation for what will hopefully be many more complex virtual heists to come.