Review for Conquests of Camelot: The Search for the Grail

Once a flourishing and prosperous land, thriving under the wise rule of King Arthur and guarded by his courageous knights, Camelot has fallen from its former glory and splendour. Embodied by the unfaithful passion between Gwenhyver and Launcelot, sin has corrupted the kingdom and plagued it with famine and drought. Gathered together at the Round Table, Arthur and his valiant fellows are visited by a vision of the Holy Grail, covered by an immaculate white drape. Launcelot, Gawaine and Galahad ride promptly away from Camelot in search of the sacred artifact, each of them seeking one of the sites in which the legend said that Joseph of Arimathea stashed the holy cup. But weeks pass, and none of them return: thus, once again advised by the deep wisdom of Merlin, King Arthur himself must quest for the Grail, last hope of salvation for his dying reign.

This appealing premise is recounted during the introduction of Conquests of Camelot: The Search for the Grail, released by Sierra in 1989 and designed by Christy Marx. Marx had met Ken Williams the previous year – “by a total fluke” in her own words – and the two of them developed the idea of a series of games inspired by the Arthurian cycle of legends, and Camelot soon became the first. Well known for her previous work on a number of comics and TV series, from Conan the Adventurer and Elfquest to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Marx did a huge amount of research to write the script of the game, blending together the main Arthurian canon – the ancient Historia Britonum, Chretien de Troyes, Sir Thomas Mallory – with Greek and Roman mythology. Covering both the Christian and pagan Grail symbolism, Marx crafted a story that, although not comparable in depth and daring with Jane Jensen’s later take on the subject, manages to be both entertaining and fascinating.

Throughout the game, beginning in England before moving to the Far East, King Arthur must overcome tough challenges on his hallowed quest. The path leading to the Grail bristles with dangers and obstacles: from the haunted forest around Glastonbury Tor to the frozen Ot Moor, the voyage of Arthur will test him both in body and mind. Finally, across the Mediterranean Sea, Arthur must prove himself worthy to receive the Grail, and thus heal his wounds as well as the ailing Camelot.

The background meticulously detailed by Christy Marx is evident from the very first steps: before leaving Camelot, King Arthur is encouraged by Merlin to study a map of southern England. Although only some of the displayed locations can be visited through the game, every important place of the region is enriched by an exhaustive description about historical events, local Anglo-Saxon saints and folklore. Every line of dialogue speaks to the extensive research of both historical and literary documentation, and even the romantic aspects of the plot – mainly the love triangle between Arthur, Gwenhyver and Launcelot – are treated in a delicate way, mindful of the laws of courtly love as arranged by the Occitan troubadours.

The characters, with their names often spelled in ancient English forms (i.e. Gwenhyver instead of Guinevere), are lavished with an equal care and even the least important supporting characters are well-rounded and realistically written. The script is also very solid: while epic and engrossing when dealing with the main quest, it displays a lighter mood from time to time. The only complaint that can be made of the plot is that the last few segments of the game feel a bit rushed and, after the closing credits, it’s evident that a direct sequel was originally planned and yet never developed. In fact, some of the early copies of the game displayed the number one, which was removed from later versions when it became clear that the next game in the series wouldn’t concern Camelot or the quest for the Grail. Although it doesn’t ruin the overall experience of the game, it’s a pity that one of the major points of the story doesn’t come to an end, leaving the player a bit disappointed. Aside from this note, the storytelling is strong and offers more than a few moments of authentic emotion.

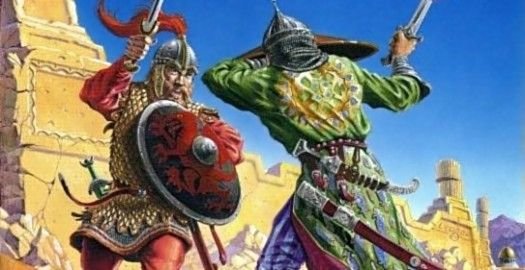

The atmosphere of the game is enhanced by its beautiful, for the time, EGA graphics. The art design was led by Peter Ledger, famous Australian artist and Marx’s husband, and his visual imagination is easily seen in the richly detailed background. Even though the game’s palette is limited to only 16 colors, there are times at which you’ll forget this: the aerial view of Camelot makes a great use of different shades of green and blue, while the violet and pearl gray grant the ice palace of the Lady of the Lake the proper eerie atmosphere. The cozy little Merlin’s study is filled with alembics, vials and other oddities such as ice crystals and long dehydrated leaves, and all these particulars are nicely polished, despite the low resolution. But where the graphics really shine is in the depiction of Jerusalem’s bazaar, which is is filled with bright, vivid colors.

Although there is no voice acting in Camelot, each location features a unique MIDI theme that manages to create a strong particular mood, from the courtly main theme to the gloomy sounds of the forest to the middle eastern score in the desert surrounding Gaza and later in Jerusalem. The soundtrack, orchestrated by Mark Seibert, always manages to be fitting. There is also one particular theme – bright and yet melancholic, in the fashion of goliardic music – that I found very addictive. Maybe that’s because I heard it a lot, as that's the one which plays when King Arthur fails one of his perilous tasks and sheds his mortal coil.

This obviously means that you can die, and in many various ways. However, unlike many other Sierra games of the period, in Conquests of Camelot death is a less random feature, as it’s always pretty clear which actions will trigger the premature departure of King Arthur. The bad news here is that death often occurs as a result of pure arcade sequences that intersperse the gameplay. These sequences vary greatly in amusement and quality: if the joust with the Black Knight is quite engaging, the boar-hunting is simply frustrating. The problem is that Camelot was made using the first version of Sierra Creative Interpreter, known as SCI0, which doesn’t match well with these kinds of segments: the keyboard commands are often unresponsive, and the mouse – otherwise available for moving Arthur around the screen – is totally disabled during the arcade sequences, making them quite difficult to master. Fortunately, the difficulty can be adjusted at any time between Hard, Medium and Easy, thus making the game far more accessible. Beware though, because the easier difficulty will lower the final score.

The point scoring system certainly isn’t new for Sierra games, but Camelot differs from its contemporaries by having three different scales: Skills points record the factual tasks, such as taking and using objects, while Wisdom points concern the dialogues, the information that can be obtained by questioning characters or looking at the environments, and puzzle solving. Finally, the Soul points measure the moral choices of the player. King Arthur frequently has to face ethical dilemmas and the decision about how to solve these situations is left entirely in the hands of the player. Most of these choices won’t affect the ending, but the quest for the Grail, at least as romanticized by medieval poets, has always been a moral one and persisting with questionable behavior might make the game unwinnable.

As for the puzzles, they’re mostly inventory-based and quite sparse. Never too difficult in their own right, the main challenge at times comes from the text parser, which is quite limited and sometimes finding the right instruction demanded by the developers can be fairly hard. In this regard, the command ‘Ask Merlin about’ is quite useful: from his tower in the fortress of Camelot, the wizard will guide every step of your quest, and the player can seek his counsel at any time. Even if the old sage has a marked preference for obscure and salacious comments, his answers often contain some vital clue on how proceed.

Early in the game, King Arthur also has to contend with riddles presented to him by enchanted menhirs, some of which can be really difficult. The whole sequence is one of the most successful in the game, however, because it forces the player to think creatively to find the answers. Later on, when King Arthur arrives at the Jerusalem bazaar, there is a prolonged sequence involving fetch quests that helps the environment to feel more alive and realistic, because every merchant has a distinct personality and a well-written, interweaved backstory. In addition, there are some puzzles solvable only through the aid of the manual, which serve as copy protection. Fortunately, these puzzles never feel out of place or contrived, instead adding a substantial depth to the background and plot.

Overall, though some of its design choices – mainly the arcade sequences and the rushed ending – are certainly objectionable, Conquests of Camelot: The Search for the Grail is otherwise a very enjoyable title, with an engaging plot, a charming, intelligent script and a wonderful (for the time, of course) graphic design. The game even runs just fine on modern machines with the aid of DOSBox, so every adventurer should give it a try, because it’s truly a little gem and one of the most underrated of Sierra’s classic games.